You have probably heard of the butterfly effect: a distant butterfly flapping its wings can have a hard-to-predict effect on a future event. Everything seems to be connected in the world, and tech companies, let alone startups, are microcosms where that seems to be even more the case.

Everything is connected

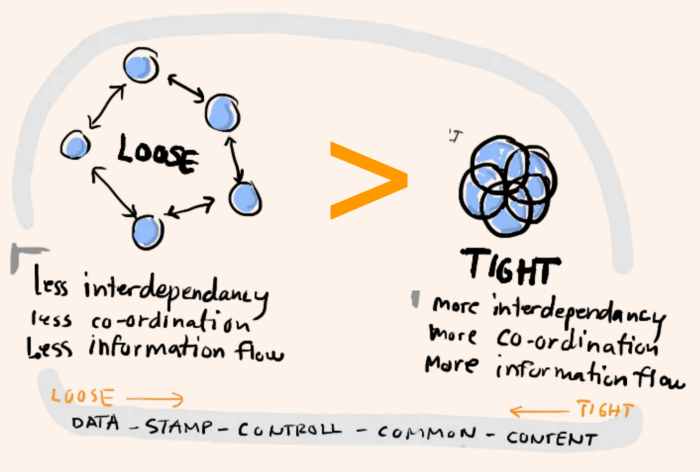

Startups make a big effort to have people focused and aligned (i.e. on the same boat). A small team means that people need to understand “everything” and be flexible to do whatever is needed. As a result of this, everything not only seems connected, but it actually is, by design. This leads to a situation where everything, from systems to processes, are completely coupled. Furthermore, coupling is valued as a positive, not as a flaw.

The benefits of coupling

Before we talk about the downsides and alternatives, it is important to acknowledge that coupling has its merits. Having everyone and everything on the same boat, if possible, means that you will be able to move faster, particularly when changing direction.

The extreme of coupling is designing everything as if it belonged to the same system. In software engineering we usually refer to this pattern as the monolith. There are different variations of the monolith, but in general you can think about designing your system as a single tier application where all code and services are interconnected and live in the same place (repository, server, etc…).

While monoliths have generally a bad press, there are again benefits with an approach where everything is in the same place and tightly coupled. It is true that nowadays people preaching the benefits of monoliths are seen as contrarians, but I would recommend you read some of what they have to say (see e.g. In Defence of the Monolith or Monoliths are the future). You will generally read about benefits like maintainability, simplicity, or efficiency. Probably the main benefit is that keeping everything connected and centralized makes it easier to reason about it (e.g. test it). It is also interesting to keep in mind that very successful and large-scale applications such as Facebook, or Quora where I led engineering, were a monolith until very late in their growth curve.

Regardless of what your philosophical stance is on the issue, it is hard to argue that no matter what your end game will be, it is usually more practical to start with a monolithic design to then evolve it into something maybe different. See what software architecture guru Martin Fowler has to say about this in his MonolithFirst pattern discussion.

But there comes a time

Whatever you think about the pros/cons tradeoffs in favor of coupling, there is an undeniable downside of a single monolithic and coupled system: there comes a time when it does not scale. The system has become too large and complex for any one person to understand it fully. Touching one piece of a tightly coupled system you don’t fully understand is a recipe for disaster since you cannot predict how it will affect the system as a whole.

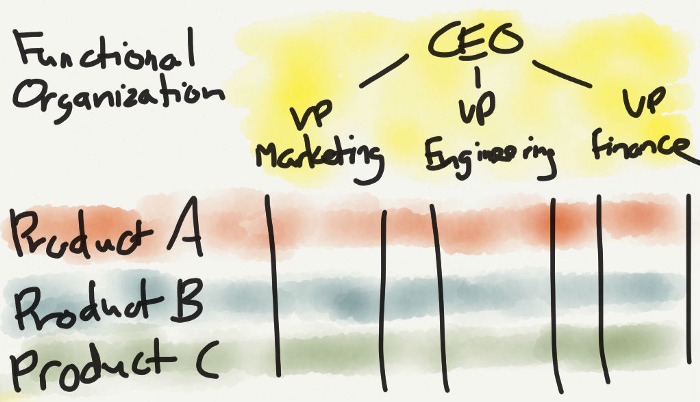

Note that what I am saying here does not apply only to a software system, but to any organizational design. For example, in a tightly coupled team everyone is expected to know the details of what everyone else is working on since there will be dependencies between everyone’s work, priorities and timelines. It should be obvious to see that this can work only up to a certain size of a team.

Everyone on the same fast and nimble boat</figcaption></figure>So, when that time comes, and it will, it should be clear that the benefits of a loosely coupled system with fewer dependencies will outweigh the ones of a tightly aligned system. When that happens, it is important to not over-react. I hear too many people that react to the monolith by going to the other extreme of microservices. Don’t get me wrong, microservice architectures are great, and it might be just what you need. But, there are also many things in between a monolith and microservices. I, for one, am a fan of starting separating services (or teams) one at a time until the need to go fully decoupled and into microservices becomes clear.

At this point it is interesting to see what others have said (and more importantly done) in the past. When doing so, it is also very important to look at those who have been successful.

On the shoulder of decoupling giants

Many highly successful companies have made of decoupling an important aspect of their culture. I will start with one close to home: Netflix.

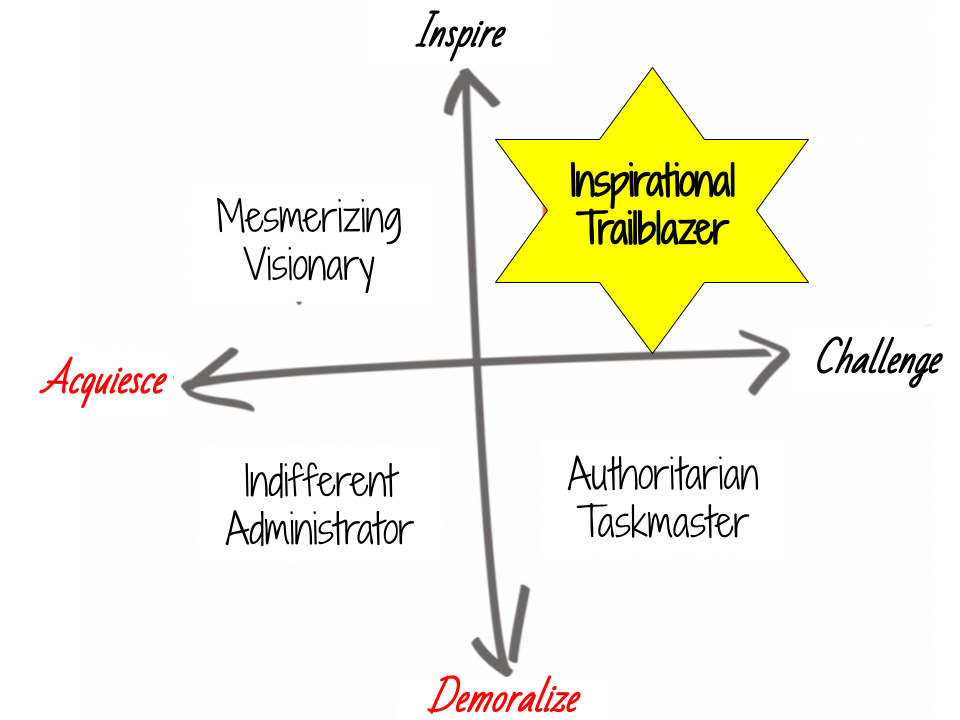

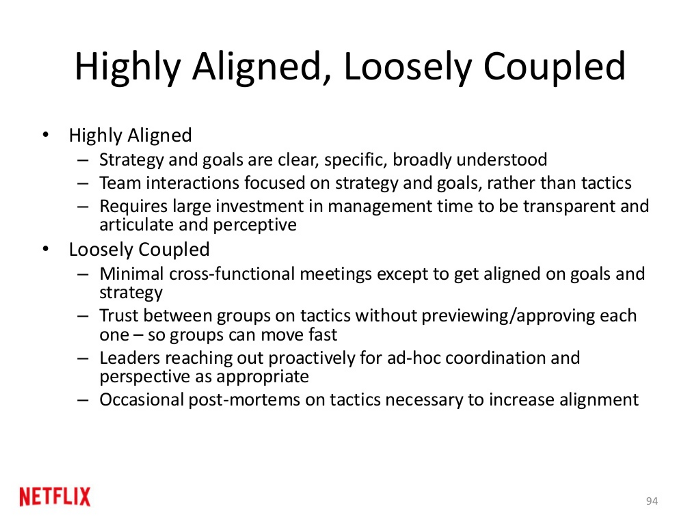

At Netflix, one of our important principles was: Highly Aligned, Loosely Coupled. You can see below the slide from the famous Netflix Culture Deck. This is a great principle since it not only touches on the importance of low coupling, but it also introduces the importance of doing so while remaining aligned. Loosely coupled teams have high level of autonomy and can move much faster independently. They can eliminate roadblocks themselves and their success does not depend on anyone else. Of course, the risk of this low coupling is that every teams moves in a completely different direction. That is why high alignment on the overall direction is so important.

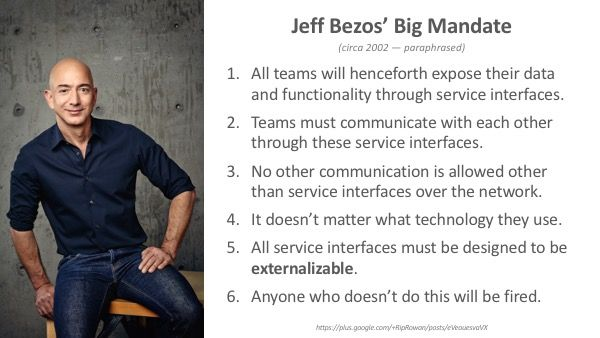

Everyone on the same fast and nimble boat</figcaption></figure>Maybe the most well known example of a company that is strong on the idea of decoupling is Amazon. The company culture in that respect is well represented in Bezos’ API mandate/manifesto from circa 2002 (see below). In this mandate, Bezos required that all teams removed all interdependencies to the point that they could only communicate through service interfaces. According to many, this is one of the secrets to Amazon’s success in scaling so much and so quickly. At the very least it is a key aspect of AWS’, and overall cloud computing, success for sure.

Somewhat related to the “Monolith first” pattern mentioned above, Reid Hoffman’s Blitzscaling describes how to start a company as a small “pirate boat” initially, but be ready to (blitz)scale at some point. When that happens, there are eight key transitions the company needs to go through:

- Small to large teams

- Generalists to specialists

- Contributors to managers

- Dialogue to broadcasting

- Inspiration to data

- Single focus to multithreading

- Pirate to navy

- Founder to leader

I have bolded the ones that are directly related to decoupling. Some of them are very obvious (e.g. single focus to multithreading), but I think there is one that is worth highlighting: from generalists to specialists. Indeed, a single generalist doing everything is the ultimate monolithic organization. Hiring only generalists assumes that “understanding everything” and being flexible is the most important aspect. However, when an organization starts embracing decoupling, it will understand that someone can be very impactful and successful while specializing on a particular aspect of what is needed.

The one notable exception

I will bring it up before you do: sure there are exceptions to decoupled organizations, perhaps the most notable being Apple. It is important to understand though that while those companies might not make decoupling a top-level value, and in fact might praise the virtues of centralization, in order to function at their scale they need to have some form of decoupling. Nobody at Apple, not even Tim Cook, understands everything that is going on at the company. Besides, more centralized organizations like Apple might be reasonable for developing artifacts like devices, but not for products or services (read more about this from Ben Thompson here).

So what can you do?

What should be your takeaway after reading all this? Well, that will depend on your concrete context and situation. As mentioned throughout this post, the exact tradeoff between loose and tight coupling will depend on your particular stage and situation. However, a few things you should always keep in mind:

- If you are starting anything out, start with a monolith with the idea that you will decouple aspects over time.

- Look out for excessive complexity or things blocking each other. This might be a sign of too much tight coupling

- Explicitly call out dependencies between systems, project, or teams at any stage.

- Do not over-react to excessive decoupling by trying to decouple everything. Find the right timing for decoupling different aspects of your “monolith”.

- Try to measure the benefits of coupling/decoupling each aspect or element in your system

- As you decouple anything, make sure that you continue to prioritize high-level alignment.

Final thoughts

As I explained in “Cultural over/under-fitting and transfer learning. Or why the “Netflix Culture” won’t work in your company.”, the ideal company culture is very context-dependent. In fact, the culture will need to evolve and adapt to each of the stages of the company growth Hoffman explains in Blitzscaling. Coupling/decoupling may be just one more of those cultural aspects, but it is an important one that can determine the degree of success. Paying attention to it is likely to pay dividends in the future.