(In case you came here looking for the spreadsheet, here it is. However, I recommend you continue reading to help you understand the overall framework.)

I am often surprised that many folks I talk to, even those working at startups, have very little understanding of how to think about the value of their equity. I should credit Chip Huyen for her post about working on a startup. While I do feel in order to make justice to that post I need to write a much broader write-up about working in a startup, the current one is addressing the discussion of how to value equity in the “You won’t get rich” section. If you are joining a startup you should probably be doing it for many other reasons than to “make money”. However, I do think it is important to have a framework to evaluate the economic value (or risk) of joining one.

What you will read here is not the result of survivorship bias of someone who’s made it big in a startup: I have yet to have a big exit from a startup (both the two startups I have been at Quora and Curai have not had an exit yet). I wish I had known more of this stuff during my time at Netflix though. I would have made much more money from my options. I will admit though that Iam a founder, and I might be biased. So, just do your research and make your personal choices. I just hope that the information in this post helps you build a better model of your prospects in a startup.

Risk, probabilities, and expected value

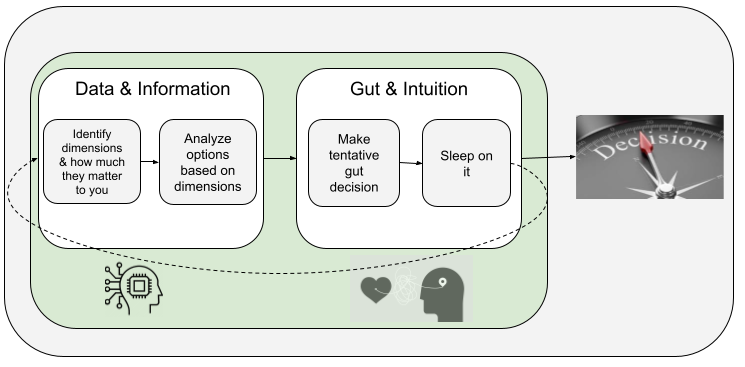

In order to value equity in a startup it is useful for you to become acquainted with the notion of expected utility and expected value. Expected utility is a economical theory and framework to make decisions under uncertainty. While there is some limitations to equating expected utility and value, this can be used as a good approximation (in reality most limitations stem from the fact that risk and probabilities are subjective, which we will talk about in the post). The expected value of an “event” is simply the value you should expect giving the possible outcomes and the probabilities for each of the outcomes.

Strictly speaking, a startup has an infinite number of possible outcomes, but you can generally simplify to a few. Just keep in mind that the probabilities need to add up to 1 and that you need to add the probabilities in bins (i.e. the probability of the outcome being 10 is going to be in reality the probability of the outcome being 0>x≤10).

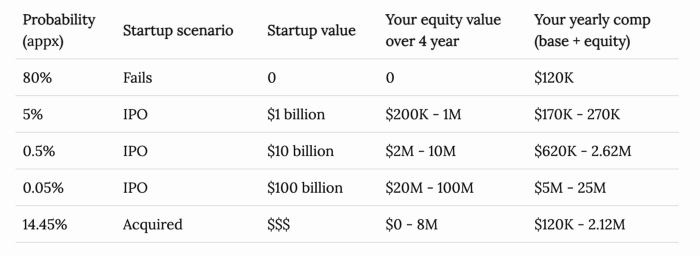

Let’s compute your yearly compensation expected value using Chip’s example (Note that in order to be as fair as possible I didn’t take the max or the min, but rather the average for each of the possible outcomes in the column on the right):

E = 0.8 x 120,000+ 0.05 x (270,000–170,000)/2 + 0.005 x (2,620,000–620,000)/2 + 0.0005 x (25,000,000–5,0000,000)/2 + 0.1445 x 2.12 = $284k

So… if we accepted those probabilities in the post to be correct, you should expect your average outcome to be around $300k a year. So, were you to assume these probabilities, and if you only cared about the actual money made, you should compare the offer you get from this hypothetical startup to an established company that offered a stable salary at around or probably above $300k. The way to think about this is the following: I am getting a compensation that is minimum $120k a year, if I am really lucky I can get up to $25M a year, but on average I should expect to get close to $300k (again, if we accept those probabilities to be correct).

It should be clear by now that a really important thing here is how you determine those probabilities. I, for example, think the probabilities in the example Chip gives above are way off in her case. Is a probability of a startup failing really 80%? Well… it depends. While it is true that the probability of a generic startup failing can be as high as 90%, this greatly depends on a multitude of factors: Is the startup in Silicon Valley or Barcelona? Are the founders technical or business experts? Do they have prior leadership experience? Is the startup backed by top VCs or came out of YC? Is the startup working on a “hot space” like AI? And so on. As an example, the article linked above already reduces the risk of failure to 75% if the startup is in the Silicon Valley and to less than 40% in some sectors. So, what happens if we move the 80% failure rate to 10% and we assign that 70% to the next likely scenario of being acquired? Well, we end up with an expected value of $985k a year… not bad. Again, I am not saying the second choice of probabilities is the right one for most situations, but it clearly will be for some. You need to work on figuring out what are the right ones in your case.

Something else for you to consider when joining a startup is that you can continuously re-evaluate those probabilities. Of course during the interview process you should try to understand as much as you can to make an informed decision, and that includes the current valuation of the company. However, no matter how much you learn before you join a startup, you are much more likely to get detailed data once you are working there. This is particularly important at early stage startups where the potential of the company can change very quickly and depends greatly on the quality of the team, which is much easier to evaluate from the inside. Keep your expected value computation at hand, and re-evaluate as you learn more about the company and the space. Speaking of which, I always recommend learning about most direct competitors and use their valuations or market caps as a good way to estimate potential outcomes. You might want to use a combination of companies in your space that have already had an exit (IPO or acquisition), and some that are closer to whatever the stage of your startup is. Another important aspect of joining a startup if you have a strong resume is that if you join and you don’t like what you learn once you are in, you can always leave. While I always hope that is not the conclusion of anyone joining my startup, the reality is that the optionality to leave adds to the upside of a startup opportunity (see this blog post for more details on this).

Strike price, vesting, fair market value, and preferred price

The discussion above is valid regardless of what kind of equity you are getting at your company/startup. However, it is key that you understand the exact details of what you are getting and how to think about it.

Generally speaking, in a startup you will get “stock options”. This is different from e.g. RSU’s that you will get at a larger company. Options should be understood as your “right to buy shares”. When you get an option, you really have nothing except the ability to buy shares, but you don’t own the shares themselves. Weird, you might say. Well, let’s understand how that works at least at a high level.

When you get an option grant, say for 1,000 options, you usually don’t get anything on day one. With your grant, you will get what is called a vesting schedule. This is basically telling you how those 1k options will be distributed over time. A typical schedule is 4 years with a one year cliff. This means that out of those 1k options, you will get 250 after your first year anniversary (cliff). You will get the other 750 monthly, over the next 3 years.

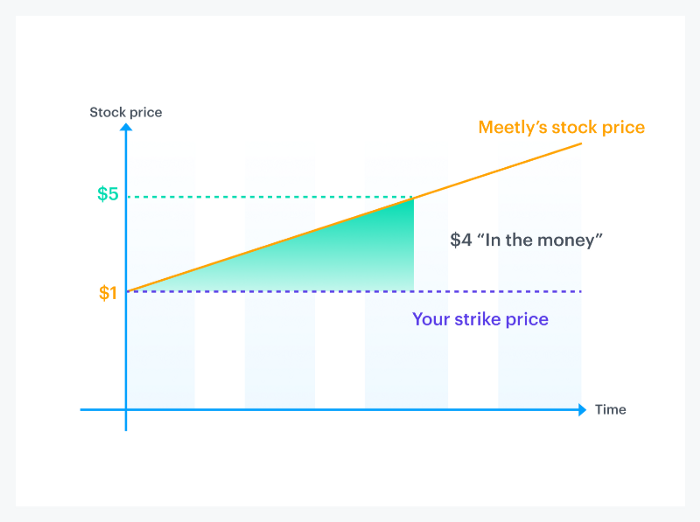

Again, when you get your options, you don’t have shares of the company. All you have is the option to buy those shares. And, what is the price you can buy your shares at? That is the strike price. The strike price is determined at the time you get your original grant by using the concept of fair market value (FMV). This is determined by a process run by a financial institution (accounting firm, bank, or even Carta) and it is called the 409A valuation. Note that the strike price for this particular grant will remain constant over time. What makes the grant valuable for successful start-ups is that over time the difference between the selling price and the purchase price will become very large (the spread).

So, how can you determine the “stock price” over time in the graph above? The reality is you can’t determine 100% until there is some form of liquidity event (see section below). However, a good approximation is to look at the (preferred) share price of the last valuation since, if things go well, that is all you need to go. If things don’t go well, investors get… well, preference. They might get their money back while employees get nothing. So, yes, this probability, however small it might be, should be factored in your 0 equity payback scenario when computing your expected value.

How should you compute the other possible outcomes for the expected value computation? Simple: take the number of options/shares times the spread (stock price minus strike price). In order to come up with possible stock prices look at comparable companies as mentioned above and find a multiplier for the current startup valuation. Don’t worry too much by how realistic they are. You can always adjust that in the probabilities! (Also, if you are wondering about dilution, we’ll discuss that later in the post)

Also, you should understand that the initial compensation package that you get when joining a startup is not the end-of-it-all. Part of your research about the company should include asking whether the company updates salaries on a regular basis, promotes, and offer grant refreshers, which are new equity grants that are issued during your tenure so that you are always vesting shares. Your first grant might just be the onramp to getting value out of company equity, and similarly your first cash salary is likely to be upgraded as you and the company grows.

Liquidity events

While you can exercise your vested options (i.e. buy shares for options that have vested) at any time, you can really only sell them for money if there is someone willing to buy. This generally only happens if there is a “liquidity event”. The most likely liquidity events for a startup are an IPO, or an acquisition. So, generally speaking you should not expect to sell (and therefore make money) before then. This is important, since, regardless of your expected value, the timeline of that expected value might affect your computations.

There are other less common liquidity events that have to do with the so-called “secondary market”.In some circumstances, startup shares might be sold before the company goes IPO or is acquired, either when the company itself chooses to offer to buy some of the shares back, or via companies specializing in selling your private shares. More recently, there are companies that specialize in selling your private shares to private buyers that are interested in acquiring them, often at a discount though (see e.g. here or here for more details).

When to exercise

So, given that you won’t be able to sell your shares until a liquidity event, you might be asking yourself why you would want to exercise your options before then. Again, exercising your options means buying the shares for your vested options at the strike price. So, you will have to pay real $$’s out of your pocket. Why would you do that? In a word: taxes.

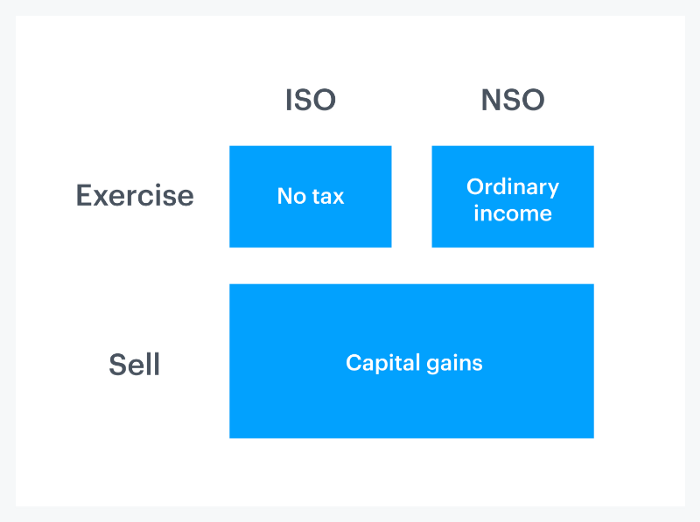

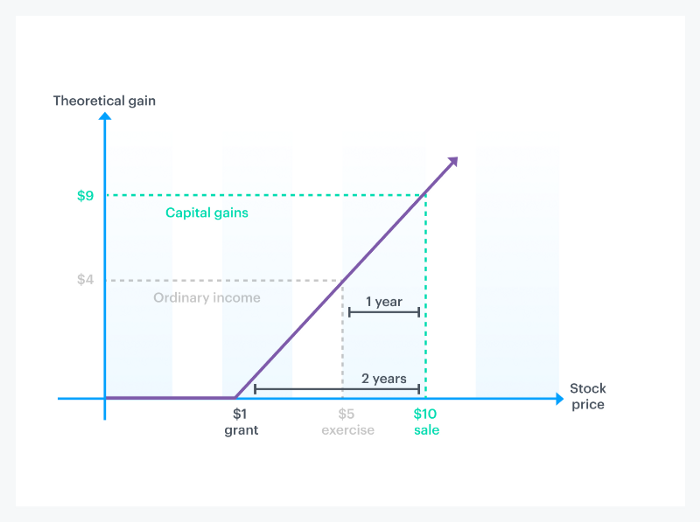

Again, it is beyond the scope of this post to go into the details of how options and shares are taxed, but it is in your best interest that you understand these details on your own (see this guide for more details). Roughly speaking though, depending on what you do you can end up paying as low as 20% in long-term capital gains, or almost double in ordinary income. That depends on a number of things, including the kind of options you have (ISO or non qualified).

If we look at ISOs (the most common case), you generally don’t have to pay taxes when you exercise (unless you trigger the alternative minimum tax) and you will pay Capital Gains when you sell. If you sell at least one year after you exercise, and two from your grant, you will qualify for long-term gains. In some cases, particularly in very early stage startups, you might even benefit from exercising options before they have even vested. In other words, you are buying something you still don’t have the rights to with the condition that you will be giving it back if you leave before vesting. This is called early exercising and is not always possible or advisable. But, it is something you might want to know about.

You should become familiar with tax implications, since they’ll be critical if the company has a successful exit.

Dilution

A common mistake made by many startup employees is to over-obsess and misunderstand dilution. The reality is that unless you are a founder or a very early employee, dilution doesn’t matter much. And, even in those cases, it only matters if handled incorrectly.

So, what is dilution anyway? Dilution is the process in which when a company issues additional shares, your overall ownership of the company gets reduced. This usually happens in the context of a new financing round. You might own 1% of the ACME startup after series A. In the next financing round, the company issues more shares to accommodate the new investors. Your 1% is no longer 1%.

That is many times interpreted as a negative. However, that is usually not the case. If the startup is growing, and the new shares are issued in the context of an up-round, the value of your options or shares is probably going to be higher than before, regardless of what percentage of the company you own! The value of your equity is always the number of shares times the price per share. And the price per shares is determined by the valuation of the company divided by the total number of shares issued. As long as that multiplier keeps going up, you are in good shape. Your percentage of ownership of the company is simply a side effect of the above and will be reduced over time. See this example in the Carta blog for more details.

So, how should you account for dilution in your expected value computation? The easiest way to think about it is the following: in order for the shares value to multiply times 10, the company valuation needs to multiply by more than 10. How much more? Hard to say. That depends on the number of rounds from now until the liquidity event and how much the company is diluted in each round. As you can see here and other answers on Quora, a typical startup will take 20–30% dilution in the initial rounds and less than 10% at later rounds. Note though that there is a lot of variability on this, so you need to look at many things to get it right. My advice is simply tweak the probabilities in the expected value to account for this. Also remember that if your compensation goes up and you get equity refreshers those are more than likely going to make up for any dilution.

It is important to note that just as it doesn’t make much sense to compare percentages of ownership across different startups, it does not make sense either to compare number of options or shares. That is just like comparing 10 American dollars to 10 Japanese yens. You should be comparing the value, not the number of bills you own!

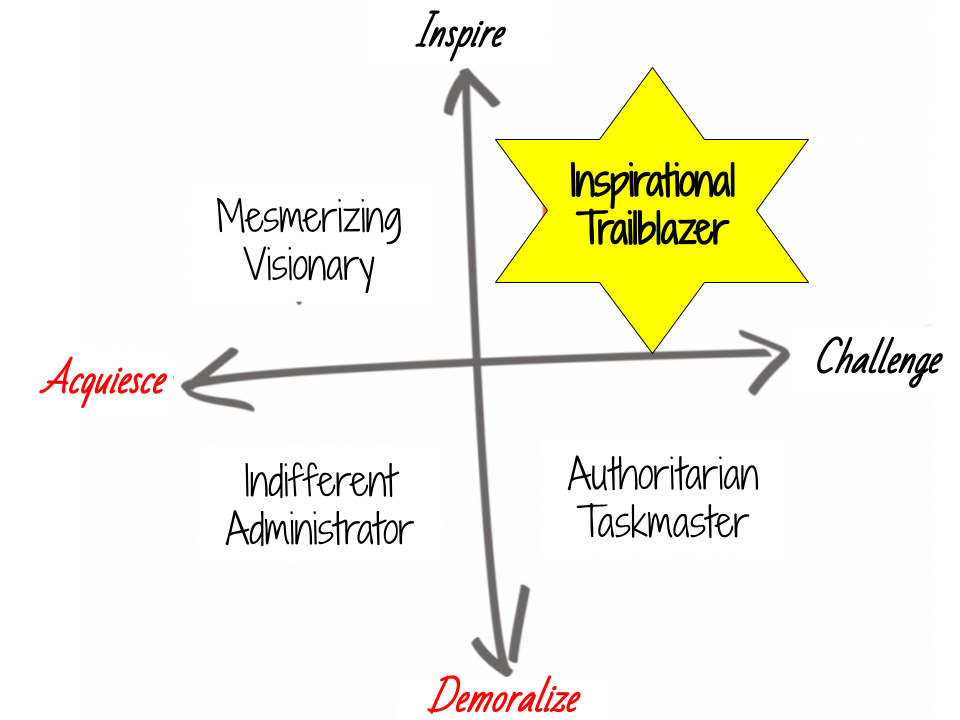

Bottom line: don’t join a startup only for the money

I hope the post has clarified how to think about the monetary opportunity of a startup. Once we got that out of the way, here’s the deal: if you are only thinking about becoming rich, don’t join a startup. While making money is a real possibility, there is also quite some risk associated with it. Plus, there is the timeliness element of having to wait for liquidity. Even if you’re just focused on money, you should consider factors with massive long-term financial impact: career growth, networking, technologies exposure, leadership opportunities. Going back to what I introduced at the beginning of this post, the utility value of you going to a startup might be in fact higher than the expected value! I hope to get into those other factors in a future post.

A spreadsheet helper

If you liked what you read, and you want to this framework, here is a simple spreadsheet for you to play around with.

Thanks

To Steve Herrod, Erik Bernhardsson, Neal Khosla, and Francois Huet for feedback on early drafts of this post.