Over a year ago, following an original presentation at MLConf, I wrote a blog post entitled “10 Lessons Learned from building ML systems”. At that point, I was leading the Algorithms Engineering team at Netflix and those lessons reflected lessons we had learned there over the last few years. When you do a post/presentation like that, you don’t really know how it is going to be received. Some things might be obvious to many while others might be controversial and some will not agree. It turns out though that it was very well received and referenced elsewhere (e.g. http://machinelearningmastery.com/lessons-learned-building-machine-learning-systems/ or http://techjaw.com/2015/02/11/10-machine-learning-lessons-harnessed-by-netflix/).

With that in mind, a year later, I now decided to follow up with 10 new lessons that built upon the original ones. The present two-part blog post includes new lessons not only learned directly at Quora but also from talking to many people at different companies.

It is worth noting that although most of these lessons are intended to be general, they do focus on user-facing internet-scale machine learning applications. All of them are definitely valid for applications such as search or recommendation. If you are working on areas like image processing or speech recognition they might be somewhat less applicable to you (would love to hear in the comments if that is the case).

10 More Lessons

Without further ado, let’s get into the first 5 new lessons.

Lesson 1. implicit signals beat explicit ones (almost always)

Many have talked about how implicit feedback is, at least in some cases, more useful than explicit feedback. For example, I wrote about this at length on a two-part post in the Netflix tech blog some time ago. There, we acknowledged that while the famous 5 stars at Netflix were a good initial simplification of the recommendation problem, there is much more to gain from other information such as what users actually decide to watch or not.

Another famous example of the same effect is Youtube moving away from their 5-star ratings into a much simpler thumbs up/thumbs down model (See here for the original blog post).

So, is implicit feedback always more useful. And, if so, why is that?

Let’s start by describing a bit better what implicit/explicit feedback is. I define implicit feedback as ”information gathered from actions not directly recognized as giving feedback by the user”. These include any action where the user is selecting, clicking, or making a choice. In other words, all those actions in which the user is not (consciously) informing the system about any preference.

One benefit of implicit data is that it is usually more dense and representative of all users and scenarios. Any product usage log is easily converted into implicit feedback. It does not require any specific action by the user. As such, it is not biased towards, for example, users who are more vocal and decide to express their preferences. Also, it does not require the user to be an expert on the product or the domain. As soon as you start using the product, you are giving implicit feedback.

Implicit feedback is also more representative of user behavior vs. user reflection. In other words, I might decide not to upvote an answer on Quora by, say, Donald Trump because I disagree with his point of view. However, that does not mean I am not interested in reading it. As a matter of fact, that piece of content might be more interesting for me to read than one that I will upvote to show sympathy or encouragement to the author. In many ways, implicit data is usually better connected to the final objective function of the product and the business. Because of this, it will also be usually better correlated with AB test result metrics.

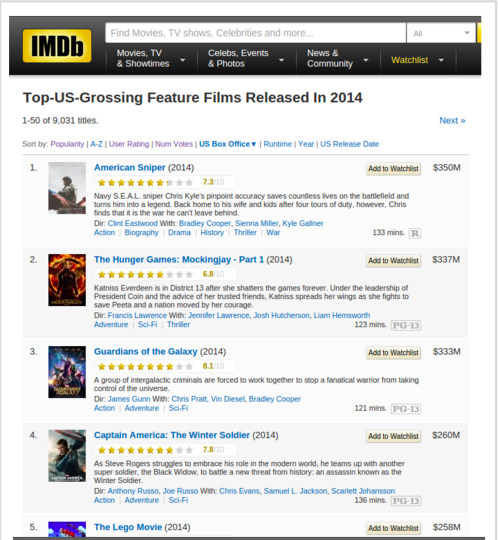

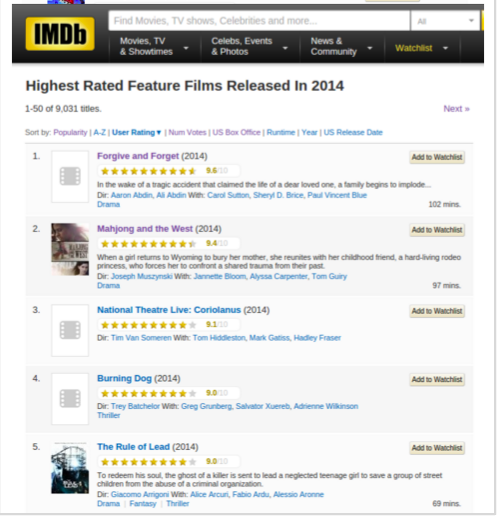

As a quick thought experiment, let’s take a look at what implicit data and explicit data tells us about films released in 2014. We’ll take box office as an implicit measure of people “preferring” a film enough to decide to go and watch it. We’ll take IMDb rating as an explicit measure of how much users like a film. If you take at the two lists below you will see what would be our top (unpersonalized) recommendations according to box office, and according to average rating. Which one would you choose? Of course, you can argue that rating average is not a good metric because niche content with very few, but good, ratings will be unfairly promoted. And, that is true. But, precisely this makes some of my previous points of how explicit data is affected by sparsity and user bias.

That said, it is not always the case that implicit feedback directly correlates well with long-term retention. A counter-example is clickbait content. You can get people to click on things that they “really did not want to click on” by showing flashy images or controversial statements, for example. Users might be “tricked” into clicking this, but later decide to leave your product because they feel they are wasting their time or do not get enough out of it. There are many examples of sites and products that have fallen into the trap of optimizing short-term metrics to then end up failing as a long-term business. Too much focus on only optimizing for implicit feedback might have that side effect. (You can read about short-term/long-term effects in AB testing in many of Ronny Kohavi’s papers).

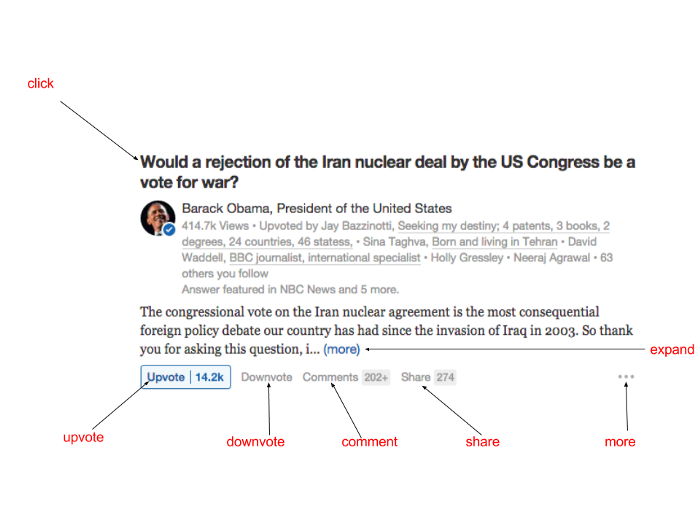

The solution is, as many times, somewhere in the middle. You can actually combine different forms of implicit and explicit data in your ML models to account for short-term engagement but also for long-term retention. If you take a look at a Quora answer, for example, you can see that there are many actions the user can do on it: they can expand, upvote, downvote, comment, and share the answer. They can even click on the originating question. We take all of these into account in our models and features and tune them to the business long term goal and mission that is represented by the AB test metrics we care about.

Lesson 2. your model will learn what you teach it to learn

Machine learning models don’t have a will of their own. They will just learn whatever you show them. In particular, machine learning models will respond to:

- Training data (e.g. implicit and explicit)

- Target function (e.g. probability of user reading an answer)

- Metric (e.g. precision vs. recall)

As a made-up thought experiment, related to the previous IMDB example, think about a scenario where we want to: “Optimize probability of a user going to the cinema to watch a movie and rate it “highly” by using purchase history and previous ratings. Use NDCG of the ranking as final metric using only movies rated 4 or higher as positives.” The information here does a pretty good job of specifying all the different constraints that we want to place on the model and what it needs to learn. Leaving any of them underspecified might lead to completely different, and maybe wrong, results. For example, if we underspecified the final metric and simply said “Use NDCG of the ranking” we might be tricking ourselves to only optimizing for the probability of going to the movie even though we are considering ratings both in the objective function and the training data.

Let’s go to another more practical example: the Quora homepage Feed:

| In this case, our training data will be a combination of implicit and explicit feedback as we mentioned above. The target function will try to capture the value of showing a story to a user by using a weighted combination of the different actions the user can take on the story. The weights will represent the contribution of that particular action to long-term company goals and will need to be tuned by combining product decisions with AB testing. We will predict the probability of each action and then compute expected value: v_pred = E[ V | x ] = ∑a va p(a | x). As for the final metric, we can use any ranking metric (or better, the ranking metric that we have measured better correlates to AB test metrics). |

Lesson 3. supervised vs unsupervised learning

I find that many machine learning practitioners I talk to are not aware of how powerful and useful unsupervised learning is. Unsupervised learning can, for example, be used to reduce sparsity and fight against the curse of dimensionality. It can also be used to turn raw data into features that can be fed into other models.

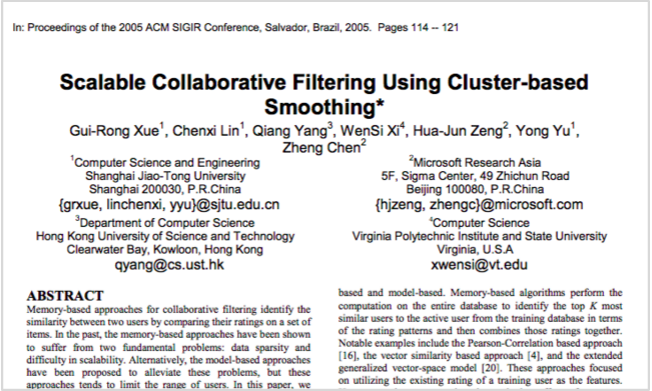

As a matter of fact, a very common practical approach to many problems is to combine an initial step of unsupervised learning with a later step of supervised learning. A simple example of this is to combine some form of clustering with basic knn in order to implement collaborative filtering (see Xue et. al, for example). The idea is simple: nearest-neighbor approaches are not efficient and rely on computing costly multi-dimensional distance functions. Clustering optimizes the approach by identifying users by their cluster and effectively reducing one of the dimensions (number of users) of the problem.

Even if you think about Matrix Factorization, you can interpret it as either supervised or unsupervised (some would call it semi-supervised). It is supervised because there are labels that you are trying to predict in a similar way as you would be doing in a regression. However, MF can also be used and interpreted as purely a dimensionality reduction approach a la PCA or as a form of clustering (this is particularly true for Non-negative Matrix Factorization, which is often used for clustering). Actually, even if you consider a standard MF approach in which training is supervised since you are trying to minimize training error to labels, the final usage can be “unsupervised”. Instead of using the label prediction output directly, you can take in the learned factors as features for another model. This is an example of using unsupervised learning for “feature engineering”.

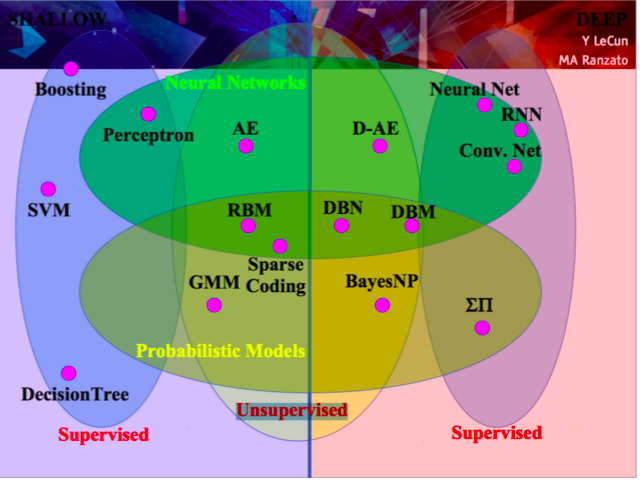

Even Deep Learning does in its own way combine unsupervised and supervised learning. Take a look at this slide from Yann LeCun’s tutorial at ICML’13 where the different (Deep) Learning approaches are classified as Supervised or Unsupervised.

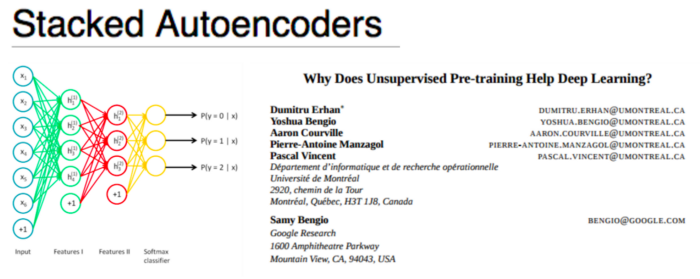

In fact, Stacked Autoencoders are an interesting way to pretain Deep ANN.

Lesson 4. everything is an ensemble

When people think about what won the Netflix Prize, they usually think about models such as SVD++ or RMBs. The truth is that the prize was won by an ensemble. Initially, the Bellkor team was using Gradient Boosted Decision Trees to combine dozens of predictors. The final ensemble used Neural Networks to combine the 103 methods.

In fact, most practical real-life machine learning applications use an ensemble approach. The question is “why wouldn’t you?”. The ensemble is going to be at least as good as the best of your methods (provided you can assume that your methods are not entirely correlated). Also, ensembles are a great way to combine very different approaches. For example you can combine content-based and collaborative filtering into a single prediction through an ensemble. And, you can use many different models in the ensemble layer (logistic regression, GBDTs, Random Forests, ANNs…).

As a matter of fact, ensembles are the way to turn any model into a feature! You don’t know if you should be using Factorization Machines, Tensor Factorization, or Recurrent Neural Networks? Why not use all of them? Treat each model as a feature and feed them into an ensemble so it figures out the relative merit of each of them. Actually, it might be that a particular model is better at predicting a particular sub-area of your problem space. A non-linear ensemble will be able to figure that out!

Lesson 5. the output of your model will be the input of another model (and other design problems)

We have seen already how ensembles can be used to turn any existing model into a feature that will be fed into another. Chances are that if you build a useful model, someone will find a way to feed it into another. This is great for reusability, but it can easily turn things into a mess.

What this means is that if you are building a model that is likely to be used in different contexts and as input to others, you need to design it in a way that it is robust to this and it is ready to accept data dependencies. For example, if you are building a ranking model, it might be wiser to publish the rank number instead of the score. This way, a change in score distribution or scale will not affect downstream dependencies.

Furthermore, as Leon Bottou described in his recent ICML keynote, you should be aware of feedback loops in you machine learning system setup.

Data dependencies and feedback loops though are just examples of a broader concern: we would like to treat our machine learning systems in a principled way just as we treat our software systems. Is that possible? The answer is yes… and no. Yes, because you should apply best software engineering practices to your machine learning systems. Concepts such as encapsulation, abstraction, cohesion, or low coupling, all have some parallel in machine learning. Sculley et al. from Google touch upon some of these principles in their (now popular) paper on the “high-interest credit card”.

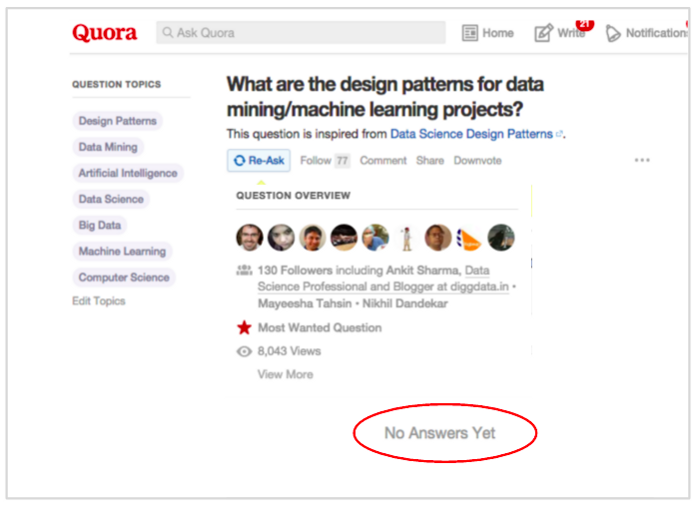

However, the problem for machine learning systems and software is that there are no well known and documented design patterns. This makes reusable and principled design much more complicated than it should. This seems to me as a very interesting area for research since there is a real need and interest and not many answers (see how this Quora question has no answer yet).

I look forward to your feedback.

Onto Part II.