A few weeks back, Netflix announced that they were adding a two thumbs up option to give feedback on their content. At the same time I was being asked on Twitter why we had given up on 5 star ratings at Netflix back in the day. Given that I have personally spent a lot of time in my career looking into ratings and user feedback, I thought I’d share some of what I have learned not only during my time at Netflix, but also before and after.

I became fascinated with user ratings like many other folks in the context of the famous $1M Netflix Prize. That dataset had a lot of interesting data, and also very unexpected findings. Lots was written about it at that time. For example, I wrote a pretty popular post around that time explaining why the assumption that ratings are in an ordinal scale might be wrong.. Many of us continued looking into the topic for years to come and even made a career of it. If you are interested in some of the many lessons I learned from that contest I wrote about it in an earlier post.

One of the things that becomes obvious as soon as you start looking at user feedback is that there is a tremendous amount of noise. The rating a user will give to an item will depend on how the item is presented, how much is remembered, or whether it is a sunny or rainy day. We wrote about it in our “I like it, I like it not” paper. In that work, we devised an experiment where we ask the same users to give feedback to the same items at three different times while controlling for some of the variables such as the order they were rating the items. The takeaway of the experiment was that the error of a user rating a movie in a 1 to 5 stars scale was “at least” of +/- 0.5 stars. This error depends on many aspects, including the rating itself since ratings in the middle of the scale (2 or 3) are consistently more noisy. It is important to keep in mind therefore that a user preference can never be considered as a “ground truth” for any predictive task. As a side note, this is one of the main thesis in Kahneman’s Noise book, which I totally recommend.

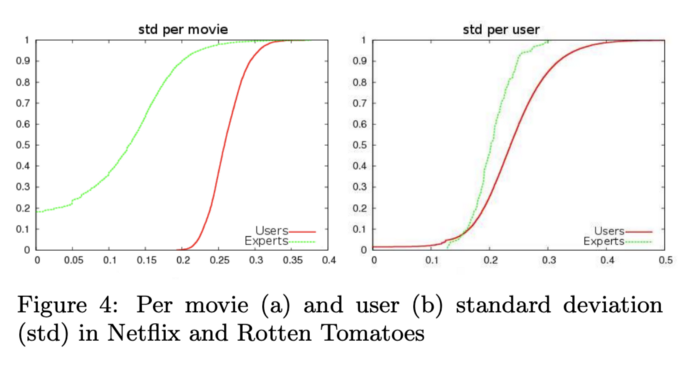

Another important aspect that affects the reliability of a rating is the expertise of the rater. Expert ratings are in general much more reliable and predictable, and, as we showed in our “Wisdom of the Few” work, they can be much more reliably predicted and therefore used as a great source of user recommendations. (Fun fact: when I was at Netflix I pitched Reed that we should buy Rotten Tomatoes. He laughed it off almost as much as when I recently pitched that Netflix should buy the local cinema theater 🙂

Ratings have all other kinds of issues that have been described in many of my talks. E.g. They are aspirational (people rate as they want to be perceived, not as they act), and depend on cultural factors: Some cultures only rate extremes, while others rate using the middle of the scale as has been found in many studies on cultural patterns in survey responses (see this paper e.g.)

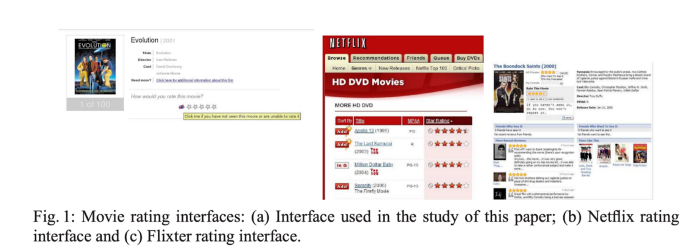

Finally, the reliability of a rating also depends on the “effort” required from the user. If you build a complicated interface that requires the user to evaluate a number of features, you will get much more reliable ratings. Of course, the flip side of this is that you will also get many LESS ratings!

This last point is extremely important, because it can be translated into the following: there is a direct tension between the amount of user feedback you will get and its quality! You can either get tons of crappy feedback from everyone, or very good feedback from a select few. Navigating that tension requires a lot of careful and dedicated UX research (you can read about such research every year in the proceedings of conferences such as CHI, Computer Human Interaction, and IUI, Intelligent User Interfaces )

So, with all this context in mind, why did ratings go away at Netflix? It should not come as a surprise: they simply became useless for how the product was operating. We started talking about it in this blog post where we already hinted about how much more reliable implicit feedback was. In general, implicit feedback (i.e. consumption signals from users) is much more reliable (it is hard to fake watching a show) and readily available from every user. Plus, it “only” requires logging (i.e. engineering work). No hard UX work and experimentation.

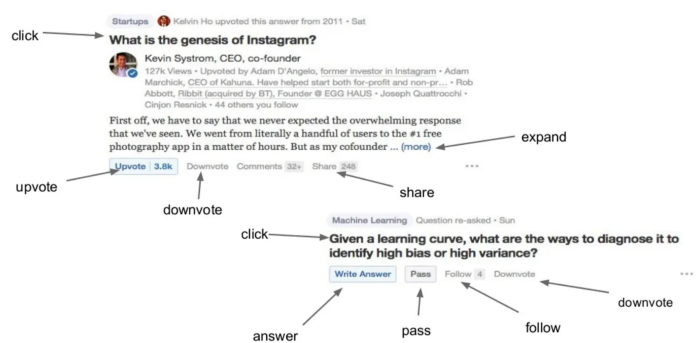

So, that was the “easy” answer, not without a lot of prior AB testing and effort in trying to rescue them. Was it the “right” answer? Well, in a product that was fully transitioning to streaming mostly on devices like TVs and, less so, mobile, it became really hard to come up with a feedback mechanism that provided just enough friction to be reliable, but not as much to make this feedback only come from an “elite” of dedicated users. I am glad to see that Netflix is now adding the two thumbs up, which means they still have not given up on explicit feedback. Other online applications such as Facebook or LinkedIn have also invested recently in enabling more nuanced explicit feedback from users. When I was at Quora, we also invested in taking into account a lot of different explicit forms of feedback such as upvotes, downvotes, expands, or shares (see presentation here).

My personal take is that explicit feedback is far more valuable than pure implicit signals that are usually only directly connected to overall engagement, but have no information about the value that users took away from the service. This is a much longer discussion though, that I will leave for a future post.